About Too Far

Q: In writing Too Far, you challenged yourself to conjure your inner six-year-old.

RS: I did two drafts of the book back in 1989 and 1990. The biggest problem I encountered was trying to remember what it was like to be six. The experience of creating a fantasy world in a natural setting—that I could recall. But a lot of the other things were difficult: I couldn’t summon up a six-year-old’s language or the practical details of what a child of that age can and can’t do. Can a six-year-old make a telephone call? I realized that I couldn’t get Too Far right unless I was very close to children of that age.

When my daughter, Sky, turned six I thought, I’d better stop what I’m doing and focus on Too Far. She lived for her fantasies, and she’d cultivated friendships with friends who have that same quality. This was my chance.

She participated in character development—not just Fristeen, but most of the other characters as well, especially Shivers. She also created the title font for the book. The story couldn’t have been written without her.

Q: What makes six so special?

RS: Something crucial happens at that age. Kids are past walking and talking, the imitation phase, the age-three declaration of independence, and so on. All the mechanical systems work. But the boundaries of the self aren’t yet frozen. The child is not clear about “what’s me and what’s not me.”

At that age, a child is capable of very sophisticated conceptions, and physically capable of real exploration. A six-year-old can go long and far, both mentally and physically. But they don’t yet understand the difference between fantasy and reality. A six-year-old doesn’t understand where the self stops and the world begins.

It doesn’t last long. My daughter is in second grade now. She’s seven, and the time of serious magic is nearly over. Fantastic creatures and imaginary companions have given way to her experiences in the real world. Eighteen months ago, she could look me in the eye and tell me that she flew behind the moon.

Q: In writing Too Far, you challenged yourself to conjure your inner six-year-old.

RS: I did two drafts of the book back in 1989 and 1990. The biggest problem I encountered was trying to remember what it was like to be six. The experience of creating a fantasy world in a natural setting—that I could recall. But a lot of the other things were difficult: I couldn’t summon up a six-year-old’s language or the practical details of what a child of that age can and can’t do. Can a six-year-old make a telephone call? I realized that I couldn’t get Too Far right unless I was very close to children of that age.

When my daughter, Sky, turned six I thought, I’d better stop what I’m doing and focus on Too Far. She lived for her fantasies, and she’d cultivated friendships with friends who have that same quality. This was my chance.

She participated in character development—not just Fristeen, but most of the other characters as well, especially Shivers. She also created the title font for the book. The story couldn’t have been written without her.

Q: What makes six so special?

RS: Something crucial happens at that age. Kids are past walking and talking, the imitation phase, the age-three declaration of independence, and so on. All the mechanical systems work. But the boundaries of the self aren’t yet frozen. The child is not clear about “what’s me and what’s not me.”

At that age, a child is capable of very sophisticated conceptions, and physically capable of real exploration. A six-year-old can go long and far, both mentally and physically. But they don’t yet understand the difference between fantasy and reality. A six-year-old doesn’t understand where the self stops and the world begins.

It doesn’t last long. My daughter is in second grade now. She’s seven, and the time of serious magic is nearly over. Fantastic creatures and imaginary companions have given way to her experiences in the real world. Eighteen months ago, she could look me in the eye and tell me that she flew behind the moon.

“A lot of my best traits—and the qualities I value most in others—come from the six-year-old self.”

The Roots of Creativity

Q: To you, the roots of human creativity go back to that point.

RS: When adults draw on the power of their imagination, I think they’re connecting with their six-year-old psyche. They’re pretending for a moment that the self has no bounds, that the mind is whatever it can imagine–that anything is possible.

A lot of the science on creativity points back to childhood. There’s a multi-generational study at UCLA, looking at achievement across all professions. So far, the conclusion seems to be that people who do well are people who have a six-year-old outlook on things. They’re playful and experiment freely. They consider themselves amateurs. Everything is an adventure with an unknown result. There are no penalties, no rules.

I have vivid memories of that age. A lot of my best traits—and the qualities I value most in others—come from the six-year-old self.

“When my imagination is burning hottest, I feel like I’m six again. So casting myself into the minds of six-year-old characters was a treat.”

The Universe Speaks

Q: From the start, you were trying to depict how the child’s imagination takes control of the mind and creates an alternate reality.

RS: My determination to do this was greatly influenced by Ibsen’s Peer Gynt, which I read for the first time during my college years and has continued with me ever since. While I was working on Too Far, I visited Ibsen’s home in Oslo. I was walking back to my hotel. I stopped, parked on some steps, and re-read the play while the sun set over the harbor.

Ibsen has the forces of the universe speak to Peer through fantasy characters. One of the wonderful things about the play is that it turns reality inside-out. All of the things that happen to Peer in the real world are less important than his interactions with the fantasy characters, drawn from Norwegian folklore. It’s in those scenes that his crises and decisions occur. The play isn’t about Peer’s struggle with other humans. It’s about his struggle with the forces of the universe and with his own character.

Robbie and Fristeen live in a world born from their minds. But that world includes characters that say things to them that they can’t fathom. That no child could fathom. I love that idea, and I believe it expresses a fundamental truth about the power of the imagination.

Q: Writing Too Far was also an opportunity for you to be six again.

RS: I lived in an imaginary world when I was that age. Later, when I was 18 and 19, there were moments on LSD when I felt like I had recaptured that same boundlessness. When my imagination is burning hottest, I feel like I’m six again. So casting myself into the minds of six-year-old characters was a treat.

Not Kids’ Stuff

Q: Despite the age of the protagonists, and the fact that it reads like a parable, Too Far is decidedly not for kids.

RS: There are books for children that work for adults. And there are books that seem to be for children, but are really for adults. Too Far belongs to the latter group.

The Wind in the Willows is a good example of a book that seems to be for children, but isn’t. It starts to work when you’re an adolescent, I think. Rat’s encounter with Pan—that’s not kids’ stuff. And all the commentary on Toad—his materialism and type-A obsessions. You need to be older to understand most of that.

Likewise with Platero and I, which found its way into my hands when I was very young. My understanding of the book has grown over the years, but it still has a lot to teach me. The language and the vignettes are so simple that it’s easily mistaken for a children’s book.

“Wilderness is creation gone crazy, doing what it feels like and making up as it goes along. For me, the wilderness is ground zero for the creative imagination.”

Perfect Love

Q: Robbie and Fristeen are as close as two children can be.

RS: It’s a perfect love. Many of us remember relationships like that. Does that kind of love become an expectation for adult relationships? To some extent, I sympathize with Grace when she tells Robbie that it’s easier for him. Grace wishes love could be like that for her. The boundlessness of the self at age six extends to friends as well. Not all kids experience this with a child of the opposite sex. But some do.

Q: This, for you, gets back to that question of the ideal world versus the practical one.

RS: Adults can get along. If they’re motivated, they can make things work. But if you’re looking for the fusion of psyches—two becoming one—kids have the edge. I think that adults who are able to realize this state are often using their six-year-old selves to get there.

Natural Magic

Q: As with your last book, Wild Animus, you set Too Far in the wilds of Alaska where, again, wild things fuel the story’s imaginative leaps.

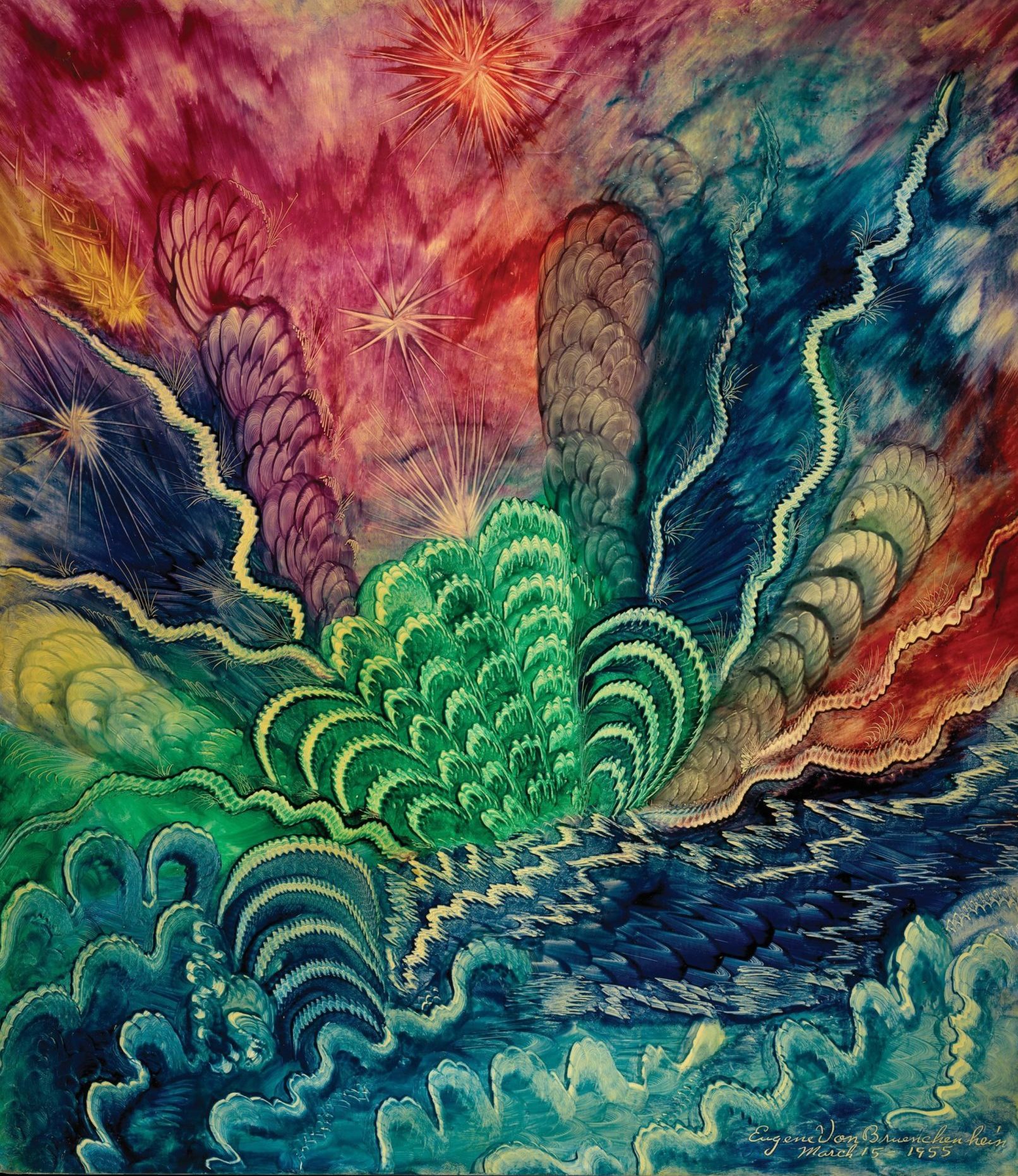

RS: People have different reasons for being in love with wilderness. I enjoy the exercise, the physical demands of the outdoors. I like exploration and natural history, and taxonomy. But what I love most is the magic.

Wilderness is creation gone crazy, doing what it feels like and making up as it goes along. For me, the wilderness is ground zero for the creative imagination. As much as I love human art, I love the art in wild things more. It’s sacred art—all the triumphs of inspiration we know from the human domain, but without human boundaries. What is wilderness but a spawn of unpredictable ideas? When I was six, I lived in Illinois, on the edge of a forest. I could walk out of the back door, into what seemed like an infinite wilderness. I felt the connection between my imagination and the imagination expressed in the wilds around me.

Risk Taking

Q: In Too Far, there are conflicting ideas about the kinds of risks children should be allowed to take.

RS: Most parents struggle with this. Children prefer to assess risks on their own. They don’t want their freedoms to be abridged, and they don’t understand that parents are programmed to be fearful. Once kids become parents, they forget all of that, and think it’s their duty to second-guess their children.

Q: Robbie’s parents have irreconcilable perspectives.

RS: There’s not much compromise or collaboration. They’re really each other’s worst enemy when it comes to providing feedback to their son.

Q: You draw on some firsthand experience here.

RS: When I was six, I got in serious trouble on two occasions while wandering around in the forest. I tried to cross a frozen river, went through the ice and got swept under. I was carrying a toy rifle, and was able to chop through the ice from underneath and pull myself onto the bank. I never told my parents.

And I got seriously lost. I don’t mean confused; I mean lost—no idea where I was and no idea how to get back. I spent the better part of a day wandering around in the woods before I finally saw something I recognized. It was terrifying.

But the freedom to explore was one of the great joys of my childhood, and it strongly influenced my identity as an adult.

Children have to take risks in order to test themselves, to experience the unknown, and to define who they are. But how do you assess danger and risk if the six-year-old imagination is in high gear, and the child has shaped the world and its rules around hopes and dreams?

Living a Dream

Q: Robbie and Fristeen first connect with another realm—the realm of their gods—in their dreams. Do dreams contain the seeds of human transcendence?

RS: I think they do. I’m very attracted by the idea that we arrive here from a dream, and when we leave we disappear into another dream—or maybe the same one. Maybe my language is inside-out: we’ve come from reality and wandered into a dream during our earthly life.

What is a dream? Among other things, dreams allow us to return to a state in which the boundaries of the self seem non-existent. For Robbie and Fristeen, the realm of dream is a portal through which their heroes reach them. It’s their dimension of escape. In many ways, their life together is a dream. The world they inhabit isn’t here, it’s there.

The Ultimate Sacrifice

Q: Dreams have the potential to transport us to other realms of being, but Robbie and Fristeen imagine something more dire.

RS: The willful destruction of our physical presence is hard for any of us to contemplate. Shivers’ perspective is that when he’s “done dining, there’s nothing left.” But the Dream Man knows better.

Perhaps the Dream Man is a sham, as Shivers says. But I love him all the same, and so does Robbie. When I asked my six-year-old daughter to give me a reality check on this, she defended the promise of escape offered by Dawn and her beau. Her argument was Cartesian: the fact that Robbie and Fristeen believe in their heroes, and have envisioned a world beyond the one they are imprisoned in, is a kind of proof that it exists.