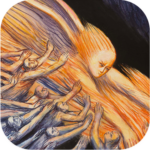

About Beneath Caaqi’s Wings

Q: This story was a surprise, coming from you. Teen Romance meets Lord of the Flies.

RS: (Laughs.) But the ending is very different. And the resolution is the kids’ doing, not something brought on by the return of Mom and Dad.

The book was written during the Covid crisis. My wife and I were in a foreign land, having fled to New Zealand, and we were forced into close quarters with our younger daughter, who was experiencing the horrors of adolescence. I realized how much mental energy I’d given, over the years, to blocking my memories of that traumatic time.

Q: You’ve shown a great fondness for childhood in some of your other novels. But the teens in this novel are a rough lot.

RS: I was motivated by the realization that many of the best human qualities—wonder, unfettered love, selflessness, boundless imagination—emerge during years three through eight; and many of our worst qualities—viciousness, bigotry, mob behavior, envy, social exclusion—blossom during adolescence.

The typical behavior for adults who pass through the ordeal unscathed, I think, is to process the memories so that the bulk of the awful stuff is removed. As a result, it’s a shock to find yourself back in the nightmare with a child of your own. Why do we pass through this? Why are such vile behaviors expressed? What is it about our makeup that requires that? Those questions, for me, were really provocative.

Q: This story was a surprise, coming from you. Teen Romance meets Lord of the Flies.

RS: (Laughs.) But the ending is very different. And the resolution is the kids’ doing, not something brought on by the return of Mom and Dad.

The book was written during the Covid crisis. My wife and I were in a foreign land, having fled to New Zealand, and we were forced into close quarters with our younger daughter, who was experiencing the horrors of adolescence. I realized how much mental energy I’d given, over the years, to blocking my memories of that traumatic time.

Q: You’ve shown a great fondness for childhood in some of your other novels. But the teens in this novel are a rough lot.

RS: I was motivated by the realization that many of the best human qualities—wonder, unfettered love, selflessness, boundless imagination—emerge during years three through eight; and many of our worst qualities—viciousness, bigotry, mob behavior, envy, social exclusion—blossom during adolescence.

The typical behavior for adults who pass through the ordeal unscathed, I think, is to process the memories so that the bulk of the awful stuff is removed. As a result, it’s a shock to find yourself back in the nightmare with a child of your own. Why do we pass through this? Why are such vile behaviors expressed? What is it about our makeup that requires that? Those questions, for me, were really provocative.

“The truth about who we are matters, and it matters as much as the truth about what the world is and how much we can change it without breaking it.”

Q: The characters find quite a few reasons to take each other down, including class, race, gender and sexuality.

RS: Any difference, really, is fair game. Maybe our interest in social justice as adults isn’t simply right behavior. Maybe it’s a vestige of guilt that we carry from an earlier age. Maybe it’s a denial of the impulses that are lurking inside us all.

Q: We’re a social species. Why is it part of our design to be so cruel to each other?

RS: That’s the question, and we need an answer. There’s no use in raging about it or imagining we can change it. We have to understand who and what we are. Our natures are not infinitely flexible based on our desires. We are enlightened enough now to recognize that we can’t make any change we like to the earth and our environment without negative consequences. But we are still making the error, I think, of imagining we can change our own natures freely without encountering similar problems.

The truth about who we are matters, and it matters as much as the truth about what the world is and how much we can change it without breaking it.

It seems to me that, in parting ways with adults and the nuclear family, teenagers have to establish a social order of their own, and that means starting with savagery and building up the rules of a functioning society.

Q: The kids’ separation into tribes based on gender was disturbing. To find harmony, both boys and girls have to cross a great divide.

RS: It’s a part of the design we focus less on these days. Our societal interest in legitimizing same-sex relationships, laudable as it is, obscures the difficulties that heterosexuals have in crossing the gender frontier.

Q: I can remember.

RS: So can I. And being the father of teenage girls gave me the motivation to look at the issues in a way I could not when I was going through them myself. The transition is difficult and anything but automatic; and it’s loaded with hostility and doubt. We should regard the teen years as a time of miracles, I think. It’s amazing, really, that crossing the gender divide and creating a “new” social order works out so well in so many cases.

Q: Everything in the story happens in the absence of adult guidance.

RS: The only higher authority is Caaqi, hardly a trustworthy chaperone.

Q: A god of sorts. I know to expect a character like that in your stories. What happens couldn’t happen without him.

RS: Like my other deities, he’s a cipher for forces inside us. We all worship the parrot god when we’re teens. And his power is greatest when he’s not screeching in our ears, telling us what to do. When his presence is subtle, when he’s planting his dreams and stirring latent desires, he can be a force for good, he can restore the order and harmony he’s taken away. We can’t throw him off, we can’t avoid the changes he works on our lives. We have to count on his mercy, which seems arbitrarily—even spuriously—delivered.

Q: For me, he was like the Polyp in Arms from the Sea in that I found myself wondering whether he was a true god or a false one.

RS: What kind of belief do most of us have during our adolescent years? It’s really a time of horrible uncertainty, of narcissism and deafness, of venting and self-aggrandizement with only a vague hope that we will have a firmer foundation some day. Caaqi has to be a transitory god. No sane person could worship a god like that for very long.

Q: Pate hears Caaqi and he internalizes him. But at the same time, Pate anticipates the maturity of adulthood.

RS: In surfacing my own blocked memories, I struggled to find myself on the teen stage. I realized that I’d had many friends, but I’d never been part of a tribe. I was Pate, because of my orphanhood. A child without parents grows up quickly, and that adulthood cuts against membership in an adolescent tribe. When I was a teen, I thought my peers were acting like children. The orphan benefits by being more lucid during adolescence, but the lucidity has a downside. There’s critical learning about social connections that the orphan observes but doesn’t experience directly. That can be crippling later in life. The time we spend beneath Caaqi’s wings, as crazy and traumatic as it is, is essential to who we are.

Q: Toward the end of the book, I began to feel like I was watching Caaqi cure some of our present-day maladies, healing the children’s wounds, and our own along with them.

RS: I had something like that in mind. Increasingly, I feel like I’m writing for some future era of man, when the fooleries have passed and it’s possible to consider the magic and the paradoxes in our design with wonder and curiosity.

Q: During my reading of the novel and listening to the Bonus Track, I wondered whether the experience of your own children’s adolescence had left a few scars.

RS: (Uncomfortable pause.) More than a few.