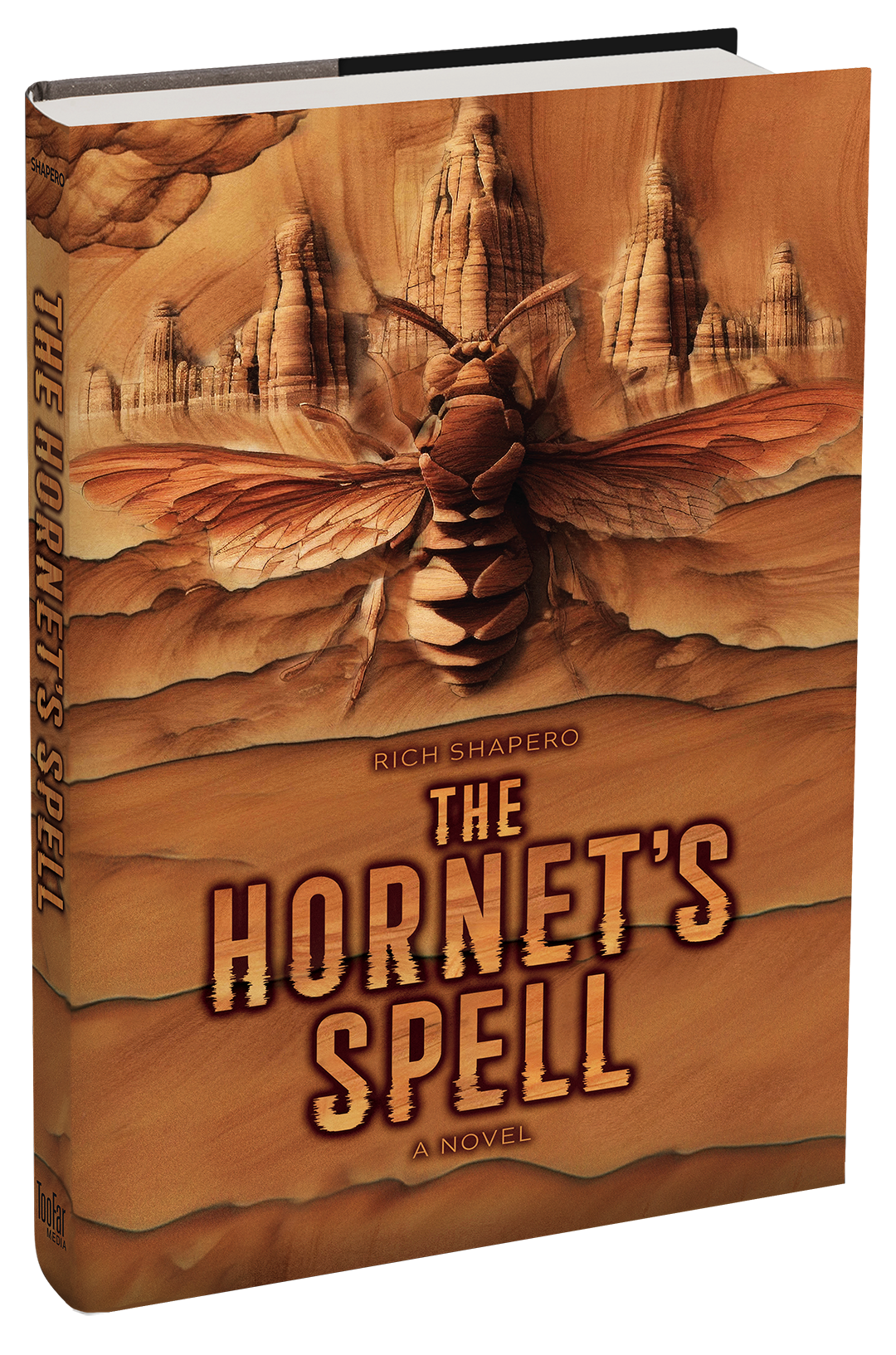

About The Hornet’s Spell

Q: The protagonist, Danni, has a problem and she’s seeking help. Do you think her problem is widespread?

RS: My daughters are young adults now, and the reports from them are bleak. We are in a Nietzschean moment, in which concerns about power predominate. Between online dating, social networks, porn, feminism, sexism, incels, gender fluidity, and the passion to rethink every norm of pre-nuptial behavior, the basic need—to declare a truce and give love a chance—has been left for dead.

“There’s a design that has nothing to do with modern social needs. Right now we’re choosing to ignore the design, in favor of testing the limits of creativity.”

Q: And that’s a mistake.

RS: The question is: what does it take for people to be happy and fulfilled? Re-fashioning ourselves is wonderfully creative, but there is an element of blindness and arrogance that comes with self-determination. Ignoring the design can be dangerous.

My third-grade teacher was an FDR liberal, a wonderful woman who believed, as many did back then, in the great blessing of civil engineering. She brought her Martin to class and taught us Woody Guthrie songs that celebrated the refashioning of the earth for the good of mankind: building bridges, moving coastlines, generating power by damming rivers. Two decades later, everything had changed. People had become conscious of the “environment,” an awareness founded on the insight that the earth had its own design, and the human race couldn’t ignore that.

I think we’ll go through the same process with gender, partnering, love and family. There’s a design that has nothing to do with modern social needs. Right now we’re choosing to ignore the design, in favor of testing the limits of creativity. At some point there will be a retrenchment. We’ll realize that we can’t change the design without repercussions. You can build a dam and generate power, but the forests downstream disappear, and so do the salmon. At the time of that realization, removing the dams and restoring the design becomes a cause of its own.

Q: I found myself asking when and where in human history there has been an ethos like the one Danni and Raj find in the spires.

RS: It’s at odds with current American and European culture, isn’t it. There were moments in the twenties when self-realization by women included a different outlook on love. And the same thing can be said about the sixties, when “free love” encouraged an openness to intimacy—not just sex. You can find similar ideas in a variety of utopian schemes. And if you go back a millennium, there’s the vision of love put forward by the sculptors of Khajuraho.

Q: Danni and Raj have to find that world on their own.

RS: They do. Danni’s personal history and the social milieu she lives in make it difficult for her to find what she’s looking for. For her, a journey is required.

Q: How much experience do you have with hypnosis?

RS: A fair amount. I’ve worked with a number of hypnotists over the years. I’ve acted out scenes for novels while under a spell. My experience has been positive. It’s all based on the suggestibility of mind, which is often surprising.

Q: The power of mind is a repeated theme in your novels.

RS: It is. I’m convinced that we underestimate our mental capacities. We will be a different species, I think, when we accept and embrace our potential.

Q: There’s a lot of sand in this book. Even before the tapestry takes Danni and Raj to a different dimension, there are references to sand everywhere you look.

RS: (Laughs.) One of the chief technical satisfactions in writing, for me, is juggling image systems. The journey of Danni and Raj takes us to a sandy place; and there, the future is sculpted in sand. Having sand raise its grains early on, in select places, seemed like a necessary part of this story.