About Xiphactinus

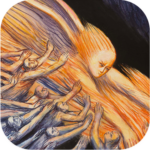

Q: Xiphactinus is a journey to hell with an artful devil.

RS: An understandable description. I have, over the years, been drawn to works with a persona like Xiphactinus. There aren’t a great many, but I would put The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Les Fleurs du Mal, and Les Chants de Maldoror on the list. And Golding’s Pincher Martin, as well.

The devil’s voice can be engaging. And when it’s speaking paradoxically, it can be liberating. In the writing, I found myself having to juggle two minds: the one that enjoyed the “ruthless” psyche, and the one that wanted to deny it.

“Keeping the moral apparatus intact while being a predator is difficult.”

Q: You think this is a reality we have to face?

RS: I do, if we’re going to understand who we are.

The most charitable view—charitable to us—is probably the biological one. Because we’re a social species, we come equipped with a complex moral apparatus. We care about right and wrong, we feel guilt and shame and obligation to others. At the same time, we evolved to be hunters—to kill other creatures to live. Keeping the moral apparatus intact while being a predator is difficult. We’re smart enough and sensitive enough to understand what it means to prey on other sentient creatures.

Q: Xiphactinus doesn’t have that problem.

RS: He doesn’t. Xiphactinus doesn’t have to draw a line between morality and predation. And when it comes to predation, he doesn’t have to ask questions about when a predatory outlook’s okay and when it is not.

As with most of the paradoxes we face, there aren’t any simple answers.

“We all have interior voices that speak to us, and we’re always listening . . .”

Q: Late in the story, a comparison is made between the voice of Jesus that Vianca hears and the voice of Xiphactinus that is omnipresent for Dun. The big fish is a kind of god for him.

RS: The interior voice—a guiding presence—is a staple of most religions for obvious reasons. We could even define religious belief as the condition in which the voice becomes a commanding presence. What may be less obvious is that we all have interior voices that speak to us, and we’re always listening, agreeing or disagreeing, involving that voice in the debates we have about our behavior and our decisions in life.

Q: A psychoanalyst would say that you’re talking about the superego. Am I right?

RS: I think you are. It’s interesting that Freud viewed it as a layer of consciousness superimposed on more basic functions. That’s undoubtedly how Xiphactinus would view our moral equipment.

“There are moments . . . that draw on things I experienced, and there are others that are purely imagined. But they all depend on some opening, some insight, that affected me strongly enough to be preserved as a gift or a scar.”

Q: You chose a strange way to present the story. The reader gets the monster, Xiphactinus, full in the face; but the real protagonist, Dun, is seen through gaps in the fish’s narrative.

RS: It was a challenge to present Dun’s story that way. But the peculiar structure yields something important, I think. As monstrous as the Xiphactinus perspective is, it was a struggle for me—and I wanted my reader to struggle—to see the traces of Dun’s humanity through it. We all live with that struggle, I think.

Q: Dun has to act like a monster to survive in a world of reptilian adversaries.

RS: As do we all. That’s part of the human challenge, especially in our era, when the security of the close-knit tribe has given way to the reality of larger, more hostile human forces. The conflict that Xiphactinus is continually pointing out to Dun—between the rules of survival in the Sea and the social rules for the hominid order—is a conflict most of us face in our daily lives.

Q: Whether we recognize it our not.

RS: It goes mostly unrecognized, I think. Which was my motivation for writing the story.

Q: Petra is a strange woman. More an enabler than a lover.

RS: A crazy enabler. She’s a powerful woman, but her power comes in an unusual form. It’s based not on savvy or earthly grounding, but on her connection to a different realm. I have a weakness for women like that. And I’m very fond of their portrayal. This is Annie in the film Gun Crazy. Or Betty in Betty Blue. Petra’s thoughts and actions are both unpredictable and dangerous. But she’s a liberator. A woman like that can change a man’s life.

Q: Rohrig, the SEC attorney, was a surprise. He’s another predator in the lawless sea.

RS: Government officials are people. They have the same needs and desires as the rest of us, and the more powerful they get, the more dangerous they are. Officials who run America’s agencies have the potential to be vicious and self-serving. In my experience, their actions are often at odds with the public interest.

Q: Dun is an unusual character, but his home life as a child isn’t extraordinary. A lot of people have to suffer through conflicts like that.

RS: They do. And detachment is often the result.

Q: Detachment from society, from simians, from other apes.

RS: If we don’t have religion or an honored place in the tribe, if we lack dignity because there are eight billion of us and we’re all dispensible, if couples prefer to live together for just a few years, what feeds a child’s conscience? How does a moral existence take root? We’ve been robbed of a lot of our self-respect, a lot of our grounding and earned pride. If we lose parental attachment, the human proposition may fail.

Q: We’ll be back to the Interior Sea.

RS: Yep.

Q: Some of the narration has the ring of personal history.

RS: As with everything I’ve done, the ideas have grown up around my experience. For me, ideas are foremost, but I’m never able to—nor do I wish to—disconnect them from the context in which they emerged. There are moments in Xiphactinus that draw on things I experienced, and there are others that are purely imagined. But they all depend on some opening, some insight, that affected me strongly enough to be preserved as a gift or a scar.

Q: The “truth” in this story is delivered with a strange mix of panache and self-condemnation.

RS: That division—that mixed emotional state—is the only truthful way I could come at the subject. We all carry a great load of guilt. Rather than denying it or hiding from it, it makes more sense to me that we would expose it and wrestle with it—give it full scope, more scope than it deserves perhaps—in order to put it into perspective. Is it possible for any of us to be truly evil? Whatever curses we carry are the products of instinct, heritage, fateful experience and flawed judgment, aren’t they? A kind nature requires a forgiving spirit, and forgiveness begins at home. In an era like ours, where the act of castigating others has become a favored pastime, Xiphactinus seemed like good medicine.