About The Hope We Seek

Q: In The Hope We Seek, you assay human aspiration.

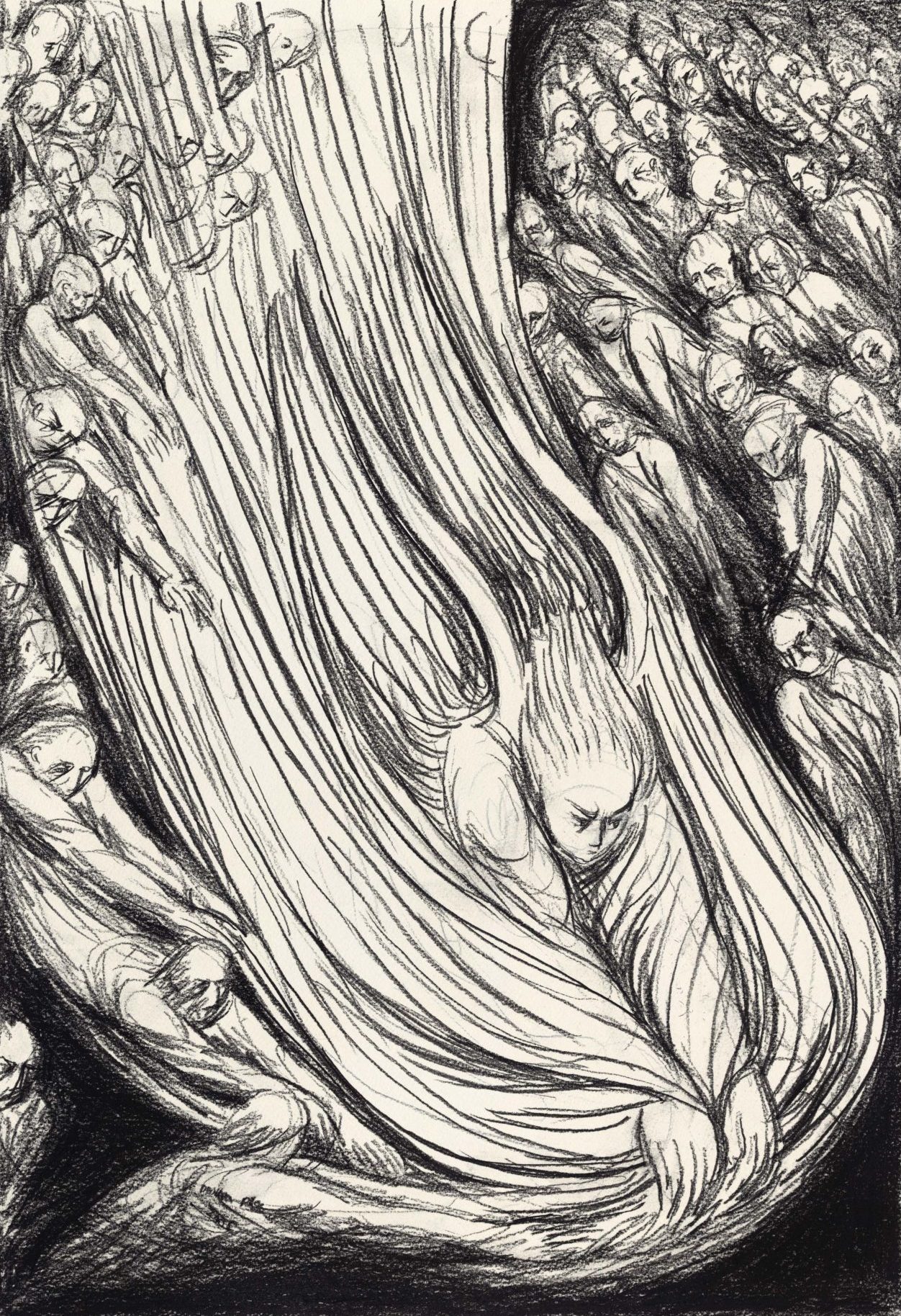

RS: There’s a clearly defined moment for most of us when we enter the adult world. Often it occurs when schooling ends. It’s a threatening time, full of doubt, fears of the unknown, fears of failure. We know it’s going to be a long road. But we have aspirations. And most of us don’t have a choice. Earning a living is a matter of survival. So despite our dread, we plunge in. We find work. The work isn’t what we dreamt of doing, but we hope it will lead to something better. Our aspirations remain with us. If we grit it out we might get there. Somehow. Some day.

I left home without a nickel. I scraped through college. My first job was digging ditches for the gas company. I worked the graveyard shift. Then I ran a printing press. I was hired by a computer company and after years in the trenches, I got the chance to run one. The company was successful. I became a venture capitalist in Silicon Valley. Ultimately, I caught up with my aspirations. But it was a long journey. The way turned and twisted, and it was mostly in darkness. The Hope We Seek is drawn from that experience.

Q: Most of us have closely-held desires, things we put in front of ourselves and say, “This is what I want.”

RS: Our culture, like most, celebrates achievement. Dreaming of a brighter future, realizing the dream, or trying to—that’s how we derive meaning from life.

Aspiration can’t exist without leadership. When a group aspires to something, a leader is chosen to fix the goal. When an individual aspires to something, there is an internal “leader”—a part of that person’s makeup that runs out ahead of the rest, to focus his or her attention and point the way.

Q: In The Hope We Seek, you assay human aspiration.

RS: There’s a clearly defined moment for most of us when we enter the adult world. Often it occurs when schooling ends. It’s a threatening time, full of doubt, fears of the unknown, fears of failure. We know it’s going to be a long road. But we have aspirations. And most of us don’t have a choice. Earning a living is a matter of survival. So despite our dread, we plunge in. We find work. The work isn’t what we dreamt of doing, but we hope it will lead to something better. Our aspirations remain with us. If we grit it out we might get there. Somehow. Some day.

I left home without a nickel. I scraped through college. My first job was digging ditches for the gas company. I worked the graveyard shift. Then I ran a printing press. I was hired by a computer company and after years in the trenches, I got the chance to run one. The company was successful. I became a venture capitalist in Silicon Valley. Ultimately, I caught up with my aspirations. But it was a long journey. The way turned and twisted, and it was mostly in darkness. The Hope We Seek is drawn from that experience.

Q: Most of us have closely-held desires, things we put in front of ourselves and say, “This is what I want.”

RS: Our culture, like most, celebrates achievement. Dreaming of a brighter future, realizing the dream, or trying to—that’s how we derive meaning from life.

Aspiration can’t exist without leadership. When a group aspires to something, a leader is chosen to fix the goal. When an individual aspires to something, there is an internal “leader”—a part of that person’s makeup that runs out ahead of the rest, to focus his or her attention and point the way.

“Humans require prophecy and vision. There is an element of fakery in that. Prophecy isn’t based on fact. It’s the deceitful vanguard of wishing and wanting. But it’s not something we can do without.”

Q: You have described a “proclamation of omniscience” that goes hand in hand with leadership.

RS: The leader says, “If we do X, then Y will be the result.” The leader doesn’t know that. He or she is guessing, hoping. The expression of certainty is a lie. But it’s a necessary lie. If we’re to throw all our energies at an aspiration, we need to know that the outcome is certain. We have to believe.

On the individual level, we need a component of our personality to see the world through tinted glasses. That interior leader says, “If you do X, then Y will be the outcome. Trust me.” And the rest of our nature signs up.

Humans require prophecy and vision. There is an element of fakery in that. Prophecy isn’t based on fact. It’s the deceitful vanguard of wishing and wanting. But it’s not something we can do without.

The miracle, of course, is where the imagined future becomes real. That justifies the guessing, the fakery, the deception. JFK says, “If we do this and that, we’ll put a man on the moon.” And one day, there’s a man walking on the moon. When the aspiration was first expressed, nobody knew if it could be realized. But the voice spoke with conviction, and people devoted themselves to the vision.

It doesn’t work for the leader—external or internal—to say, “I’m not sure we can do this. There are obstacles. There are questions I don’t have answers for. Maybe we should give it a whirl. What do you think?” That’s not leadership.

“As impoverished and desperate as these folks are, in one sense, they’re as enlightened as humans can be, because they’ve bought the thesis that they’re not on earth to cash in. The goal isn’t gold.”

Q: Leadership implies power, doesn’t it?

RS: It’s leadership that matters. Without leadership, there is no power. People can argue about whether or not a leader’s goals are worthy, but power can’t exist for itself. It won’t be tolerated. One of the obvious proofs is the reaction we all have to a certain breed of politician. When it becomes clear that a politician’s only motivation is to retain power, and that his or her positions on key issues are infinitely flexible, the politician loses the tribe’s support.

For the individual, a change in the “interior” leader can pull someone’s personality inside out. We’ve all seen that. A vision of the future proves false, the inner leader is pulled down, and the person finds a new leader inside himself or herself, with a new prophecy to fulfill.

During my years in tech, I saw this relationship between leadership and prophecy acted out on a daily basis. When the alpha wolf says, “Follow me, I know where we’ll find caribou,” he’s doing the same thing as the product conceptualist who says, “ Follow me, if we build this product, people will buy it.” Neither the wolf nor the man can see the future. The essence of leadership is prophecy, and the foundation of prophecy is—hope.

Q: When Zack reaches Breakaway, it doesn’t take him long to see that the miners are motivated by something other than material worth. In Breakaway, gold is “Hope.”

RS: Many of us associate gold with greed. Some would say that the pursuit of gold, by its very nature, is degenerate. Trevillian, the boss of the mining camp, challenges Zack to disconnect the two. He asks Zack to embrace the idea that gold is belief.

As impoverished and desperate as these folks are, in one sense, they’re as enlightened as humans can be, because they’ve bought the thesis that they’re not on earth to cash in. The goal isn’t gold.

The way it’s framed, of course, their existence in Breakaway is a desperate one. But finding Hope, experiencing her face to face—well, they seem to think it’s worth it.

Q: The people of the story worship a female deity, Hope. She’s their object of belief and desire.

RS: We come into the world dependent on a mother. A lot of our energy goes into conquering that dependence. The paradox is that when you look at the end point of aspiration—the goal—it’s usually expressed as a return to that dependent state. A state in which the trauma of constant wanting and striving is no longer necessary. That’s our idea of Eden.

During my years as a working stiff, I met a lot of determined people, people who labored for years to achieve something. What was that something? It always went beyond the short-term goal of victory in the marketplace or the creation of a healthy business—beyond what we define as financial and personal “success.”

The goal was something you might express as a sigh—a sense that “then” the struggle would be over. When asked to characterize “then,” the picture would get fuzzy or ludicrous. Leisure fantasies—idling on a golf course, sipping a drink on a yacht. Material fantasies. Sexual fantasies. The imagined end point is always one in which the objects of desire come effortlessly, without a struggle.

It’s natural, apparently, for people to imagine that a particular achievement has the power to deliver them to an idyllic state, very much like the one they enjoyed before entering the world. We imagine that this state can be reestablished in adulthood and that it can be made to persist for the remainder of our lives.

Q: Leadership implies power, doesn’t it?

RS: It’s leadership that matters. Without leadership, there is no power. People can argue about whether or not a leader’s goals are worthy, but power can’t exist for itself. It won’t be tolerated. One of the obvious proofs is the reaction we all have to a certain breed of politician. When it becomes clear that a politician’s only motivation is to retain power, and that his or her positions on key issues are infinitely flexible, the politician loses the tribe’s support.

For the individual, a change in the “interior” leader can pull someone’s personality inside out. We’ve all seen that. A vision of the future proves false, the inner leader is pulled down, and the person finds a new leader inside himself or herself, with a new prophecy to fulfill.

During my years in tech, I saw this relationship between leadership and prophecy acted out on a daily basis. When the alpha wolf says, “Follow me, I know where we’ll find caribou,” he’s doing the same thing as the product conceptualist who says, “ Follow me, if we build this product, people will buy it.” Neither the wolf nor the man can see the future. The essence of leadership is prophecy, and the foundation of prophecy is—hope.

Q: When Zack reaches Breakaway, it doesn’t take him long to see that the miners are motivated by something other than material worth. In Breakaway, gold is “Hope.”

RS: Many of us associate gold with greed. Some would say that the pursuit of gold, by its very nature, is degenerate. Trevillian, the boss of the mining camp, challenges Zack to disconnect the two. He asks Zack to embrace the idea that gold is belief.

As impoverished and desperate as these folks are, in one sense, they’re as enlightened as humans can be, because they’ve bought the thesis that they’re not on earth to cash in. The goal isn’t gold.

The way it’s framed, of course, their existence in Breakaway is a desperate one. But finding Hope, experiencing her face to face—well, they seem to think it’s worth it.

Q: The people of the story worship a female deity, Hope. She’s their object of belief and desire.

RS: We come into the world dependent on a mother. A lot of our energy goes into conquering that dependence. The paradox is that when you look at the end point of aspiration—the goal—it’s usually expressed as a return to that dependent state. A state in which the trauma of constant wanting and striving is no longer necessary. That’s our idea of Eden.

During my years as a working stiff, I met a lot of determined people, people who labored for years to achieve something. What was that something? It always went beyond the short-term goal of victory in the marketplace or the creation of a healthy business—beyond what we define as financial and personal “success.”

The goal was something you might express as a sigh—a sense that “then” the struggle would be over. When asked to characterize “then,” the picture would get fuzzy or ludicrous. Leisure fantasies—idling on a golf course, sipping a drink on a yacht. Material fantasies. Sexual fantasies. The imagined end point is always one in which the objects of desire come effortlessly, without a struggle.

It’s natural, apparently, for people to imagine that a particular achievement has the power to deliver them to an idyllic state, very much like the one they enjoyed before entering the world. We imagine that this state can be reestablished in adulthood and that it can be made to persist for the remainder of our lives.

“For anyone who works above ground, the concept of spending ten hours a day beneath the earth . . . is unnerving. It’s a different world.”

Q: The Breakaway mining camp has its prostitutes, but their services aren’t merely carnal. They dangle a spiritual carrot for the men, and that carrot echoes some age-old forms of devotion.

RS: Depicting these women as surrogates of Hope might seem odd, but the idea has precedents in human history—the idea that a woman, by using her body, can mediate a connection to the divine.

The oracles at Delphi had a dedication to Apollo that was absolute. Some were so intoxicated by fumes emanating from the temple floor that they died. There are quite a few examples of faiths in which women acted as spirit guides, as temple prostitutes, as mediums to connect male worshippers with the divine. In one sense, Breakaway is a cult—a perversion of human culture. But there may be some who see in the camp a bit of their own lives. A man might think, “I get up in the morning, I go to work, and when I return from that hell, I get a taste of heaven from my wife.” His wife might say, “He endures those torments every day, and when he returns, it’s my job to connect him with something better.” Leave It To Beaver may be just around the corner from Breakaway.

Q: Like your other books, The Hope We Seek has its own metaphysics. There’s a personal god at the center of the story.

RS: I guess that’s my thing. It’s the thing for a lot of people: a higher power, and the treasure that resides in finding that connection. The only difference is that the characters in my stories are pathologically independent. So the gods are their own.

It’s pretty common these days to see caucasians from a Judeo-Christian background who have embraced Buddhism or Native American beliefs. You can visit places like, say, Sitka or Scammon Bay, Alaska, and meet Native Americans—Tlingits and Eskimos—who have a personal relationship with Christ. These different visions of the divine are all profound, in their own way. But they may seem stale and lifeless to people who’ve grown up with them. To be powerful, the connection has to be personal and fresh. Newly revealed. All the revitalizations of Christianity—the Puritan and Pentecostal movements, for example—tossed out old ideas and practices, and found a new, personal connection with the divine.

That’s what my characters are doing. For me, it’s exciting that the god they embrace isn’t a god that has a wide following. And I like the idea—very much—that the reader gets to sort out whether he or she thinks the god of The Hope We Seek is false or real.

Q: The gods in your stories make demands on your protagonists. But they reserve the harshest terms for adults. There’s a level of violence or “insanity” required for Zack to connect with Hope.

RS: As the author, I would like to tell you that it’s up to me. But it’s not. The terms of engagement between Hope and her worshippers are determined by Hope. My role is to observe the interactions and record them. In Too Far, the Dream Man and Dawn had conditions for Robbie and Fristeen—and they weren’t easy conditions. But I won’t argue the point—Hope’s conditions are harsher.

The divine is more painful for adults, I guess. The Australian aborigines have the idea that we come from dreamtime and return to it when we die. The dreamtime idea is consistent with what science has learned about fetal dreaming. It turns out that the human fetus is in REM state throughout gestation. And newborns sleep and dream much more than adults. Maybe connecting with the transcendent is something that’s native to the fetus and the young child, but is increasingly unnatural as we get older.

Q: At the end, is Zack’s favored status with Hope any more secure than Trevillian’s was?

RS: Trevillian is angered by Hope’s inconstancy. There are those who would accuse her of being fickle. I’m not going to do that. I’m not going to defend her or malign her. Hope is Hope.

Q: Was her behavior over the course of the story simply a matter of executing a leadership change for the mining camp?

RS: Obviously Hope is long-lived, and the men who lead the effort to pursue her are not. Not only are they mortal, but the period of time during which they are capable as priests is limited. They must have physical strength and endurance, as well as the energy and personal charisma to inspire belief. They must have a passion to sacrifice themselves, and the callousness or cruelty to sacrifice others. It’s reasonable to assume that Trevillian and Zack were neither the first nor the last of Hope’s priests.

Q: You chose to set much of The Hope We Seek in a gold mine, underground.

RS: We’ve built a life, what we call civilization, out of the raw materials of the earth. Hard rock mining is a palpable expression of that. Drilling holes, burrowing into the ground, taking out materials and assigning value to them as a way of marking our own worth—I like that idea.

And I like the activity itself—the muscularity of the work and the mechanical devices that were used. In terms of physical toil and risk, the visceral sense of power conferred by dynamite and steel—well, digital electronics don’t measure up. The character of the American West was stamped by miners and prostitutes, much more so than cowboys or indian scouts. It’s a big part of who we are—this business of going into the earth and taking treasure out of it. The way in which that was done, the extremity of risk, the personal commitment— It’s all very gripping to me.

My wife and I visited mines in Alaska and the Pacific Northwest—both working mines and abandoned mines—along with the ruins of old mining camps from the turn of the century. We enjoyed that a lot.

For anyone who works above ground, the concept of spending ten hours a day beneath the earth—as the people of Breakaway do—is unnerving. It’s a different world. I lived in Virginia for a while and I did some spelunking there. And I wandered around in cave systems in the New River area of West Virginia. Underground all day, lowering yourself down narrow chimneys, crawling on your belly through twisting tunnels. It’s crazy.

I like taking myself and my readers into different worlds. The world underground is very different, and very true to the idea of the story. Different, but strangely familiar. Most of us find ourselves in Breakaway, sooner or later. We stand in the manskip and stare into the main shaft, while some monster like Trevillian—within us or without—pulls the bell rope to signal the hoist operator. Take your seat, grab the shoulders in front of you. You’re headed down.